How do Orthodox Christians pray in the year 2022? The official prayers of the Russian Orthodox Church during Russia’s war against Ukraine.

Ирина Пярт

PhD, ассоциированный профессор Тартуского университета, факультет теологии и религиоведения. Руководитель научного проекта «Православие как солидарность», поддержанного эстонским научным фондом (PRG1599).

Originally, this paper has been presented to IOTA Mega-Conference in Volos in January 2023.

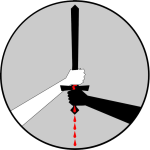

In February 2023 priest Ioann Koval’, a clergyman of the Moscow diocese, was suspended from his parish priest’s duties by order of the Moscow Patriarchate. He had to read during the liturgy a prayer circulated by the church authorities. But in the petition ‘Rise, O God, to the aid of Thy people, and grant us Thy mighty victory’ he replaced the word ‘victory’ with the word ‘peace’. The case has received broad media coverage, especially since it has been linked with another decision of the patriarchate to temporarily suspend father Andrei Kordochkin, an outspoken critic of the pro-war position of the ROC, from the parish of Mary Magdalene in Madrid.

In the words of Petro Bilaniuk, “Each prayer is a mysterious reality in the order of action with very far-reaching consequences in the semantic, logical and ontological orders. Besides, each prayer reflects the cultural, spiritual, psychological, ethnopsychological, philosophical, religious forms, heritage, etc. of the one who prays.” 1Petro Bilaniuk, Some remarks concerning a theological description of prayer, Greek Orthodox Theological Review (1976): 21:3, 203-214. In other words, despite the lofty mystical theology of prayer in the Orthodox church, one should keep in mind that any prayer is an act of communication that has rich semiotic content and cannot be taken apart from the social, political, and ideological context. In the case of prayers during the war with Ukraine, the task of the theologian is to contextualise prayers within the politics and culture of their time and critically analyse the theological concepts that underlie such prayers.

A prelude to the war prayers of 2022

First, let’s look back at 2014 when the ROC and Patriarch Kirill launched the prayer against violence in Ukraine. On 23 February, the Day of the Judgement, an address of PK and special prayers were supposed to be read in all cathedrals. Patriarch Kirill read them himself in Archangel Michael’s church in Troparevo near Moscow.

During the petition the deacon read the following prayer:

«We pray to you, O merciful Lord, to hear and have mercy on the people of the land of Ukraine (v strane Ukrainstei) and to make it indestructible from those who are creating strife (sotvoriti iu nepreoborimu ot raspri tvoriashchikh).

For the light of Your divine wisdom to enlighten the minds of those who are darkened, to strengthen Your faithful in the land (zemle) of Ukraine and to preserve them unharmed, we pray to You, Almighty Creator, hear and have mercy on them.

Grant us to fulfil your commandment to love you, our God and our neighbour, so that hatred, enmity, resentment, bribery, bloodshed and other lawlessness may cease, and true love may reign in the people of the land of Ukraine, we pray you, our Saviour, hear us and have mercy on us».

Kneeling before the throne, the Primate of the Russian Orthodox Church prayed for Ukraine:

«Almighty God, Sovereign and Sustainer of all creatures, filling all with Your majesty and sustaining it with Your power.

We adore You, our sovereign Lord, with a broken heart and fervent prayer for the land of Ukraine, which is riven with strife and turmoil.

Merciful and Almighty Lord, do not be filled with wrath. Be gracious to us, we pray to You, Lord Jesus, the author and finisher of our salvation. Strengthen with Your power faithful people in the country of Ukraine; enlighten with Your divine light the eyes of those who are going astray, so that they may understand Your truth; soften their bitterness; quench their enmity and unrest which is rising against the country and its peaceful people, so that they may know You, our Lord and Savior. Do not turn Your face away from us, O Lord; give us the joy of Your salvation. Remember the mercies You showed our fathers, turn Your anger into mercy, and give Your help to the Ukrainian people who are in distress.

The Church of Russia prays to Thee, presenting to Thee the intercession of all the saints who have shone forth in her, more than the Most Holy Mother of God and Ever-Virgin Mary, who from ancient times have covered and defended our lands. Warm our hearts with the warmth of Thy grace, establish our will in Thy will, that as of old, so also now may Thy all-holy name be glorified, the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost, forever and ever. Amen.»

This prayer needs to be understood in the context of Euromaidan, a protest that lasted for several months, the centre of which was the Independence Square (Maidan Nezalezhnosti), and that resulted in many victims on both sides. On 22 February the Supreme Parliament (Rada) issued the statement that the President had resigned and so the power belonged to the Parliament. The armed forces and police took an oath to the new government. So, when on 23 February Patriarch Kirill read the prayer to stop the violence, he was reacting to events that had been taking place since the previous November. The Church interpreted the political change in Ukraine as a violent and illegitimate act, which was the official position of the Russian government. Patriarch called all bishops to pray on their knees on that day, after Kirill’s address was read. In order to understand the prayer, we – applying the theory of communication, have to understand the code, common to the addresser and addressee. The meaning is “Maidan is a human action that is displeasing to God because it violated the legitimate authority, as a result God might punish them with their wrath, but the Church intercedes on behalf of all, including those who might be blind to see the truth, so that their eyes will be open”.

The act of prayer itself is important too. Prayer cannot be just composed and published in a book, or on a website, it has to be prayed. PK prays in the altar of the church on his knees. This indicates the significance of the act: the patriarch prays on his knees only during Pentecost.

The message that is sent by this act of communication: the events in Ukraine have enormous significance for the church (patriarch prays on his knees), these events might bring God’s wrath on the people; the graveness of the situation is the result of people’s disobedience to legitimate authority. Don’t act like them.

In this prayer the euphemism Holy Rus’ was not yet being used. PK uses interchangeably ‘the land’ (zemlia) and ‘the country’ (strana) of Ukraine which betrays his confusion about the political status of Ukraine.

Protests against the new post-Maidan authority began in the eastern parts of Ukraine, Donbass and Luhansk regions, turning these industrial, depressed areas into hotbeds of separatism, even though in the spring of 2014, there were various forms of cultural autonomy on the table. The movement received the title of the ‘Russian Spring’. It resulted in the annexation of Crimea with the participation of the Russian military in disguise, and in the emergence of militarised units in Donbass that claimed de-facto control of the region. Since Russia’s financial and military aid of the ‘Russian spring’ was well-acknowledged, the western countries implemented economic sanctions. The role of the ROC in the ‘Russian spring’ is yet to be discussed, especially its impact on the right-wing sections of the church.

In response to the conflict in 2014 the Moscow patriarchate prescribed a prayer to be read in all parishes, supposedly authored by Metropolitan Sergii of Ternopol (Ukraine).

A prayer for peace and overcoming of internal strife

Lord Jesus Christ our God, look with your merciful eyes on the grief and the painful cries of your children in the land of Ukraine.

Deliver Your people from civil strife, quench the bloodshed, and turn away the troubles that lie ahead. Give shelter to the homeless, feed the hungry, comfort the weeping, and reconcile the divided.

Don’t let your flock be ravaged by the <arms> of relatives who are in bitterness (в озлоблении сущих), but give you speedy reconciliation, as you are generous. Soften the hearts of the hardened and turn them to your knowledge. Grant peace to Thy Church and her faithful flock; that with one heart and one mouth, we may glorify Thee, our Lord and Savior forever and ever. Amen.

In this prayer, the addresser is synonymous with the people of Ukraine, and the prayer identifies himself or herself with the suffering subject. The context of the prayer is the military and social actions between separatists and the Ukrainian armies, which led to the suffering of the people of Ukraine, who are presented as one family experiencing a rift. The code of this prayer is the family: any conflict within society can be described as a family. Ukraine, both the East and the West are one family. If we keep in mind the prayers of 2022, we see a huge difference: the conflict in Ukraine is presented as a family affair even if some relatives are presented as ‘being in bitterness’, not they are not described as ‘foreign tribes’.

This prayer was circulated from the Moscow patriarchate to all parishes within and outside Russia, and as far as is known, in 2014, it was read in MP parishes.

The end of the ‘family affair’? The official prayers in 2022

The conflict in Donbas was receding in 2020 and 2021. Yet, using the pretext that Ukraine was preparing for an invasion, on 24 February 2022 the Russian Federation invaded Ukraine. Just one week into the invasion, on 3 March 2022, patriarch Kirill read a new prayer, which was then prescribed to all parishes of MP by the circular letter of Metropolitan Dionisii.

Prayer for the Restoration of Peace

O Holy God, Most Gracious Lord, Jesus Christ our God, by the prayers of our Most Pure Lady Theotokos and Ever-Virgin Mary, of the holy Equal-to-the-Apostles Grand Duke Vladimir and Grand Duchess Olga, of the holy New Martyrs and Confessors of our Church, Our venerable and godly fathers Antony and Theodosius, wonderworkers of the Kiev Lavra of the Caves, Sergius, hegumen of Radonezh, Job of Pochaev, Seraphim of Sarov and all the saints; make our prayer favourable for the Church and for all Your people.

From the one baptismal font which was at the time of holy Prince Vladimir, we Thy children have received grace: establish in our hearts a spirit of brotherly love and peace forever!

Forbid and overthrow plans of the foreign tribes, desiring to be at war and to fight against Holy Russia.

By Your grace guide those in authority to all good, strengthen the soldiers in Your commandments, bring the homeless to their homes, nourish the hungry, strengthen and heal those who are in affliction and suffering, give those who are in confusion and sorrow good hope and comfort, and give to those who have been killed in battle the forgiveness of sins and blessed repose.

Fill us with the faith, hope and love that we may confess to Thee, our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, with Thy everlasting Father, Thy Holy and Life-giving Spirit, in one word and with one heart, for ever and ever. Amen.

In contrast to the prayer of 2014, Patriarch Kirill uses here the expression Holy Rus`. The first public occasion when Patriarch Kirill proclaimed that Russia, Ukraine and Belarus are Holy Rus` took place during the concert in Kyiv dedicated to the 1020th-anniversary of the Baptism of Rus` in 2008 2Thanks to Andrey Shishkov who has drawn my attention to this event.. Since then this trope has become recurrent in his public presentations.

The saints listed in the prayer are significant both for Kyiv Rus` as well as Muscovite Russia. The appeal to Holy Rus` is a response to Putin’s official aim to free the Ukrainian people from Nazism. Appealing to the mythical Holy Rus`, the prayer makes a symbolic denial of Ukrainian self-determination: even in comparison to the prayer of 2014, Ukrainian nation-making is no longer an internal family affair, but the direct concern of the Russian state. The message of the prayer is clear: Holy Rus` is under threat, and our common heritage is now being attacked and needs to be defended.

On 25 September 2022, when the military mobilization was underway, Patriarch Kirill read the new prayer, which clearly expressed support for the military operation. Considering the sermons of the church’s leader, in which he compared death in the war to the sacrifice of Christ, there is no surprise that the new prayer explicitly calls for victory over the enemies of Holy Rus’.

Prayer for Holy Russia (25.09.2022)

O Lord God of might, God of our salvation, look with mercy upon Your humble servants, hear and have mercy upon us: behold, those wishing to fight turned against Holy Russia, wishing to divide and destroy the unity of her people.

Rise, O God, to the aid of Thy people, and grant us Thy mighty victory.

Assist your faithful children who are zealous for the unity of the Russian Church, and strengthen them in the spirit of brotherly love, and deliver them from their troubles.

Forbid them that in the darkness of their minds and hardness of their hearts tear Your garment which is the Church of the living God, and overthrow their designs.

By Your grace guide those in authority to all good things and enrich them with wisdom.

Strengthen the soldiers and all defenders of our homeland in Your commandments, give them the strength of spirit, and keep them from death, wounds, and captivity.

Bring home to those who are homeless and in exile, give strength to those who are hungry, strengthen and heal those who are afflicted, give good hope and consolation to those who are in confusion and sorrow.

Give forgiveness of sins and blessed repose to all who were killed in these days, and of wounds and diseases.

Fill us with the faith, hope, and love that we have in Thee; and raise up once more in all the countries of Holy Rus` (во всех странах Святой Руси) peace and harmony, and renew love one for another among Thy people, that with one mouth and one heart we may confess unto Thee, One God in Trinity glorified. For thou art intercession, and victory, and salvation to them that trust in Thee, and to Thee we praise, Father, and Son, and Holy Ghost, now and ever, and unto the ages of ages. Amen.

The difference of this prayer from the previous ones is that it clearly defines the referent, i.e. on behalf of whom the prayer is made (the army, the state) and also clearly defines the purpose with maximum benefits for the referents: “strengthen, bless, multiply, save, reconcile enmity, establish peace, forgive sins to those who laid down their lives in the war for the Orthodox faith”.

Commentators on this prayer paid attention to the expression «warriors and all defenders». Andrey Kuraev asked whether it meant that in addition to the Russian Armed Forces, someone else was conducting military operations. And who might that be? He guessed that these might be the Rosgvardiya and the private feudal armies of Kadyrov and Prigozhin. (Kuraev’s FB commentary of 13 November)

The prayer is made on behalf of the arbitrarily defined referent, Holy Russia which is described both territorially (all countries of Holy Rus`, presumably including Belarus) and spiritually ‘the unity of the Russian Church’. The Russian Church is presented here as an actor responsible for the salvation of the faithful in all countries of Holy Russia. Mythmaking is typical for patriarchal hymnography.

Aleksander Kravetsky considers that the trope of Holy Rus` is a relatively late addition into hymnography. According to him, it only appears in the prayer service to Hermogen of Moscow written between 1913 and 1917, most likely under the influence of the celebration of the 300th-anniversary of the Romanov family. During this jubilee, the expression Holy Rus’ has become a synonym of the Russian state.

Furthermore, Holy Rus’ has become popularised by the sticheron from the prayer service to All Russian Saints, composed by St Afanasii Sakharov in the 1940-50s. According to Sergei Chapnin, this has become an Orthodox meme:

“The new House of Euphrates, the chosen land, Holy Rus’, keep the Orthodox faith, by it, you will be strengthened! (Rus` Sviataia, derzhi veru pravoslavnuiu)”. 3A. Kravetsky and E. Pociechina, eds. Minei: obrazets gimnograficheskoi literatury i sredstvo formirovania mirovozzreniia pravoslavnykh, Olsztyn: Centrum Badan Europy Wshodnjei, 2013, p. 85. See also J. Strickland, The Making of Holy Russia: The Orthodox Church and Russian Nationalism before the Revolution Jordanville, New York, 2013.

According to Kravetsky, Holy Rus’ is a concept that came to hymnography via the literary discourse from folklore. The active use of Holy Rus’ starts during the romantic nationalist period of Russian literature in the nineteenth century, in particular the works of Vassilii Zhukovskii, Zagoskin and neo-Slavophiles.

Therefore, the use of HR in the patriarch’s prayers suggests that it builds on the tradition associated with romantic nationalism and the period of re-sacralization of the monarchy in the last years of the Russian Empire 4 See the article of Gregory Freeze on re-sacralization of Romanovs monarchy. G. Freeze, Subversive piety: Religion and political crisis in Late Imperial Russia, Jornal of Modern history 68 (1996): 308-350. In Russian Фриз. Г. Губительное благочестие: религия и политический кризис в предреволюционной России// «Губительное благочестие: Российская церковь и падение империи. СПб: Издательство Европейского ун-та, 2019. . To be more precise, contemporary liturgical and homiletic production is a bric-a-brac activity that has no clearly articulated theological and ideological program.

A response to the official prayers by the parishes

The prayer of March 2022 was supposed to replace one that came into use in 2014, but in many parishes this prayer has not been accepted. The prayer of 2014 – with some modifications – continues to be read in the parishes of the churches under the jurisdiction of MP outside Russia, for example, in Estonia. The reason is that it is perceived as neutral, focused on the suffering subject, and any person, regardless of their position as to the war, can impose their own meaning into the words of prayer.

There is the same situation in Russia. In St Petersburg in December 2022, for example, 4 parishes continued to use the prayer adopted in 2014. In one parish, the priest reads the prayer of St John of Shanghai instead of the one proscribed by the patriarchate. In Moscow, at least one parish has completely ignored the official prayers and used the prayers of St Afanasii (Sakharov) instead. Another Moscow parish adopted the prayer of St Nicholas Velemirovich (also popular among some parishes outside Russia). Needless to say, both of these Moscow parishes are led by liberal priests.

What are the consequences for those who refuse to pay lip service to the turbo-patriotic formats of the official hymnography? Apart from Koval’s case, we know that in Moscow diocese, a parish dean has paid for his refusal to recite the official prayer by losing his post as dean (nastoiatel’stvo). The second parish priest, twice as young as the former dean, has been appointed as the parish dean.

The action of Koval’ who replaced the word ‘victory’ with the word ‘peace’ is semiotically similar to the actions of the civil activists who use the word ‘peace’ in various forms of anti-war protest.

The charges of fakes and defamation of the military forces are applied to Russian citizens who write the word ‘war’, even using asterisks and euphemisms such as vobla (dry fish) instead of the word ‘voina’ (war). However, Koval’s case is different. It challenges the patriarch’s intention to signal to the state that there is mass support for the war among the clergy and Orthodox Christians. So far, much attention has been paid to Patriarch Kirill’s homiletics, but hymnographic creativity has not yet been analysed. The reaction to the actions of individual priests sends a message to other clergy showing them the consequences. In many cases, the priests are denounced by their own parishioners or by ‘vigilant’ members of the community, as took place in Madrid.

Conclusion

Under the conditions when sociological analysis of popular opinion in Russia towards the war is not possible, the attitude of the priests within Russia towards the official position of Patriarch Kirill remains untransparent. There are different scenarios: some priests choose neutral prayers, such as the ones we have discussed earlier, others read the official prayers, and others even provide additional patriotic prayers and digital prayer space for the relatives of the soldiers.

This analysis of the hymnography of Patriarch Kirill from 2014 to September 2022 shows the change of the subject of prayer, the people of Ukraine – from the image of a family affected by internal strife (Ukraine has been seen as the same kin, but still separate from Russia), to the image of one body of Holy Rus which is penetrated by alien forces. The shift is entirely compatible with the official ideology of Putin’s official justification of the war and raises the immediate question of moral responsibility of not only the Moscow patriarchate but also individual clergy and parishioners who actively use such prayers.

- 1Petro Bilaniuk, Some remarks concerning a theological description of prayer, Greek Orthodox Theological Review (1976): 21:3, 203-214.

- 2Thanks to Andrey Shishkov who has drawn my attention to this event.

- 3A. Kravetsky and E. Pociechina, eds. Minei: obrazets gimnograficheskoi literatury i sredstvo formirovania mirovozzreniia pravoslavnykh, Olsztyn: Centrum Badan Europy Wshodnjei, 2013, p. 85. See also J. Strickland, The Making of Holy Russia: The Orthodox Church and Russian Nationalism before the Revolution Jordanville, New York, 2013.

- 4 See the article of Gregory Freeze on re-sacralization of Romanovs monarchy. G. Freeze, Subversive piety: Religion and political crisis in Late Imperial Russia, Jornal of Modern history 68 (1996): 308-350. In Russian Фриз. Г. Губительное благочестие: религия и политический кризис в предреволюционной России// «Губительное благочестие: Российская церковь и падение империи. СПб: Издательство Европейского ун-та, 2019.

Ирина Пярт

PhD, ассоциированный профессор Тартуского университета, факультет теологии и религиоведения. Руководитель научного проекта «Православие как солидарность», поддержанного эстонским научным фондом (PRG1599).

Originally, this paper has been presented to IOTA Mega-Conference in Volos in January 2023.

In February 2023 priest Ioann Koval’, a clergyman of the Moscow diocese, was suspended from his parish priest’s duties by order of the Moscow Patriarchate. He had to read during the liturgy a prayer circulated by the church authorities. But in the petition ‘Rise, O God, to the aid of Thy people, and grant us Thy mighty victory’ he replaced the word ‘victory’ with the word ‘peace’. The case has received broad media coverage, especially since it has been linked with another decision of the patriarchate to temporarily suspend father Andrei Kordochkin, an outspoken critic of the pro-war position of the ROC, from the parish of Mary Magdalene in Madrid.

In the words of Petro Bilaniuk, “Each prayer is a mysterious reality in the order of action with very far-reaching consequences in the semantic, logical and ontological orders. Besides, each prayer reflects the cultural, spiritual, psychological, ethnopsychological, philosophical, religious forms, heritage, etc. of the one who prays.” 1Petro Bilaniuk, Some remarks concerning a theological description of prayer, Greek Orthodox Theological Review (1976): 21:3, 203-214. In other words, despite the lofty mystical theology of prayer in the Orthodox church, one should keep in mind that any prayer is an act of communication that has rich semiotic content and cannot be taken apart from the social, political, and ideological context. In the case of prayers during the war with Ukraine, the task of the theologian is to contextualise prayers within the politics and culture of their time and critically analyse the theological concepts that underlie such prayers.

A prelude to the war prayers of 2022

First, let’s look back at 2014 when the ROC and Patriarch Kirill launched the prayer against violence in Ukraine. On 23 February, the Day of the Judgement, an address of PK and special prayers were supposed to be read in all cathedrals. Patriarch Kirill read them himself in Archangel Michael’s church in Troparevo near Moscow.

During the petition the deacon read the following prayer:

«We pray to you, O merciful Lord, to hear and have mercy on the people of the land of Ukraine (v strane Ukrainstei) and to make it indestructible from those who are creating strife (sotvoriti iu nepreoborimu ot raspri tvoriashchikh).

For the light of Your divine wisdom to enlighten the minds of those who are darkened, to strengthen Your faithful in the land (zemle) of Ukraine and to preserve them unharmed, we pray to You, Almighty Creator, hear and have mercy on them.

Grant us to fulfil your commandment to love you, our God and our neighbour, so that hatred, enmity, resentment, bribery, bloodshed and other lawlessness may cease, and true love may reign in the people of the land of Ukraine, we pray you, our Saviour, hear us and have mercy on us».

Kneeling before the throne, the Primate of the Russian Orthodox Church prayed for Ukraine:

«Almighty God, Sovereign and Sustainer of all creatures, filling all with Your majesty and sustaining it with Your power.

We adore You, our sovereign Lord, with a broken heart and fervent prayer for the land of Ukraine, which is riven with strife and turmoil.

Merciful and Almighty Lord, do not be filled with wrath. Be gracious to us, we pray to You, Lord Jesus, the author and finisher of our salvation. Strengthen with Your power faithful people in the country of Ukraine; enlighten with Your divine light the eyes of those who are going astray, so that they may understand Your truth; soften their bitterness; quench their enmity and unrest which is rising against the country and its peaceful people, so that they may know You, our Lord and Savior. Do not turn Your face away from us, O Lord; give us the joy of Your salvation. Remember the mercies You showed our fathers, turn Your anger into mercy, and give Your help to the Ukrainian people who are in distress.

The Church of Russia prays to Thee, presenting to Thee the intercession of all the saints who have shone forth in her, more than the Most Holy Mother of God and Ever-Virgin Mary, who from ancient times have covered and defended our lands. Warm our hearts with the warmth of Thy grace, establish our will in Thy will, that as of old, so also now may Thy all-holy name be glorified, the Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost, forever and ever. Amen.»

This prayer needs to be understood in the context of Euromaidan, a protest that lasted for several months, the centre of which was the Independence Square (Maidan Nezalezhnosti), and that resulted in many victims on both sides. On 22 February the Supreme Parliament (Rada) issued the statement that the President had resigned and so the power belonged to the Parliament. The armed forces and police took an oath to the new government. So, when on 23 February Patriarch Kirill read the prayer to stop the violence, he was reacting to events that had been taking place since the previous November. The Church interpreted the political change in Ukraine as a violent and illegitimate act, which was the official position of the Russian government. Patriarch called all bishops to pray on their knees on that day, after Kirill’s address was read. In order to understand the prayer, we – applying the theory of communication, have to understand the code, common to the addresser and addressee. The meaning is “Maidan is a human action that is displeasing to God because it violated the legitimate authority, as a result God might punish them with their wrath, but the Church intercedes on behalf of all, including those who might be blind to see the truth, so that their eyes will be open”.

The act of prayer itself is important too. Prayer cannot be just composed and published in a book, or on a website, it has to be prayed. PK prays in the altar of the church on his knees. This indicates the significance of the act: the patriarch prays on his knees only during Pentecost.

The message that is sent by this act of communication: the events in Ukraine have enormous significance for the church (patriarch prays on his knees), these events might bring God’s wrath on the people; the graveness of the situation is the result of people’s disobedience to legitimate authority. Don’t act like them.

In this prayer the euphemism Holy Rus’ was not yet being used. PK uses interchangeably ‘the land’ (zemlia) and ‘the country’ (strana) of Ukraine which betrays his confusion about the political status of Ukraine.

Protests against the new post-Maidan authority began in the eastern parts of Ukraine, Donbass and Luhansk regions, turning these industrial, depressed areas into hotbeds of separatism, even though in the spring of 2014, there were various forms of cultural autonomy on the table. The movement received the title of the ‘Russian Spring’. It resulted in the annexation of Crimea with the participation of the Russian military in disguise, and in the emergence of militarised units in Donbass that claimed de-facto control of the region. Since Russia’s financial and military aid of the ‘Russian spring’ was well-acknowledged, the western countries implemented economic sanctions. The role of the ROC in the ‘Russian spring’ is yet to be discussed, especially its impact on the right-wing sections of the church.

In response to the conflict in 2014 the Moscow patriarchate prescribed a prayer to be read in all parishes, supposedly authored by Metropolitan Sergii of Ternopol (Ukraine).

A prayer for peace and overcoming of internal strife

Lord Jesus Christ our God, look with your merciful eyes on the grief and the painful cries of your children in the land of Ukraine.

Deliver Your people from civil strife, quench the bloodshed, and turn away the troubles that lie ahead. Give shelter to the homeless, feed the hungry, comfort the weeping, and reconcile the divided.

Don’t let your flock be ravaged by the <arms> of relatives who are in bitterness (в озлоблении сущих), but give you speedy reconciliation, as you are generous. Soften the hearts of the hardened and turn them to your knowledge. Grant peace to Thy Church and her faithful flock; that with one heart and one mouth, we may glorify Thee, our Lord and Savior forever and ever. Amen.

In this prayer, the addresser is synonymous with the people of Ukraine, and the prayer identifies himself or herself with the suffering subject. The context of the prayer is the military and social actions between separatists and the Ukrainian armies, which led to the suffering of the people of Ukraine, who are presented as one family experiencing a rift. The code of this prayer is the family: any conflict within society can be described as a family. Ukraine, both the East and the West are one family. If we keep in mind the prayers of 2022, we see a huge difference: the conflict in Ukraine is presented as a family affair even if some relatives are presented as ‘being in bitterness’, not they are not described as ‘foreign tribes’.

This prayer was circulated from the Moscow patriarchate to all parishes within and outside Russia, and as far as is known, in 2014, it was read in MP parishes.

The end of the ‘family affair’? The official prayers in 2022

The conflict in Donbas was receding in 2020 and 2021. Yet, using the pretext that Ukraine was preparing for an invasion, on 24 February 2022 the Russian Federation invaded Ukraine. Just one week into the invasion, on 3 March 2022, patriarch Kirill read a new prayer, which was then prescribed to all parishes of MP by the circular letter of Metropolitan Dionisii.

Prayer for the Restoration of Peace

O Holy God, Most Gracious Lord, Jesus Christ our God, by the prayers of our Most Pure Lady Theotokos and Ever-Virgin Mary, of the holy Equal-to-the-Apostles Grand Duke Vladimir and Grand Duchess Olga, of the holy New Martyrs and Confessors of our Church, Our venerable and godly fathers Antony and Theodosius, wonderworkers of the Kiev Lavra of the Caves, Sergius, hegumen of Radonezh, Job of Pochaev, Seraphim of Sarov and all the saints; make our prayer favourable for the Church and for all Your people.

From the one baptismal font which was at the time of holy Prince Vladimir, we Thy children have received grace: establish in our hearts a spirit of brotherly love and peace forever!

Forbid and overthrow plans of the foreign tribes, desiring to be at war and to fight against Holy Russia.

By Your grace guide those in authority to all good, strengthen the soldiers in Your commandments, bring the homeless to their homes, nourish the hungry, strengthen and heal those who are in affliction and suffering, give those who are in confusion and sorrow good hope and comfort, and give to those who have been killed in battle the forgiveness of sins and blessed repose.

Fill us with the faith, hope and love that we may confess to Thee, our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, with Thy everlasting Father, Thy Holy and Life-giving Spirit, in one word and with one heart, for ever and ever. Amen.

In contrast to the prayer of 2014, Patriarch Kirill uses here the expression Holy Rus`. The first public occasion when Patriarch Kirill proclaimed that Russia, Ukraine and Belarus are Holy Rus` took place during the concert in Kyiv dedicated to the 1020th-anniversary of the Baptism of Rus` in 2008 2Thanks to Andrey Shishkov who has drawn my attention to this event.. Since then this trope has become recurrent in his public presentations.

The saints listed in the prayer are significant both for Kyiv Rus` as well as Muscovite Russia. The appeal to Holy Rus` is a response to Putin’s official aim to free the Ukrainian people from Nazism. Appealing to the mythical Holy Rus`, the prayer makes a symbolic denial of Ukrainian self-determination: even in comparison to the prayer of 2014, Ukrainian nation-making is no longer an internal family affair, but the direct concern of the Russian state. The message of the prayer is clear: Holy Rus` is under threat, and our common heritage is now being attacked and needs to be defended.

On 25 September 2022, when the military mobilization was underway, Patriarch Kirill read the new prayer, which clearly expressed support for the military operation. Considering the sermons of the church’s leader, in which he compared death in the war to the sacrifice of Christ, there is no surprise that the new prayer explicitly calls for victory over the enemies of Holy Rus’.

Prayer for Holy Russia (25.09.2022)

O Lord God of might, God of our salvation, look with mercy upon Your humble servants, hear and have mercy upon us: behold, those wishing to fight turned against Holy Russia, wishing to divide and destroy the unity of her people.

Rise, O God, to the aid of Thy people, and grant us Thy mighty victory.

Assist your faithful children who are zealous for the unity of the Russian Church, and strengthen them in the spirit of brotherly love, and deliver them from their troubles.

Forbid them that in the darkness of their minds and hardness of their hearts tear Your garment which is the Church of the living God, and overthrow their designs.

By Your grace guide those in authority to all good things and enrich them with wisdom.

Strengthen the soldiers and all defenders of our homeland in Your commandments, give them the strength of spirit, and keep them from death, wounds, and captivity.

Bring home to those who are homeless and in exile, give strength to those who are hungry, strengthen and heal those who are afflicted, give good hope and consolation to those who are in confusion and sorrow.

Give forgiveness of sins and blessed repose to all who were killed in these days, and of wounds and diseases.

Fill us with the faith, hope, and love that we have in Thee; and raise up once more in all the countries of Holy Rus` (во всех странах Святой Руси) peace and harmony, and renew love one for another among Thy people, that with one mouth and one heart we may confess unto Thee, One God in Trinity glorified. For thou art intercession, and victory, and salvation to them that trust in Thee, and to Thee we praise, Father, and Son, and Holy Ghost, now and ever, and unto the ages of ages. Amen.

The difference of this prayer from the previous ones is that it clearly defines the referent, i.e. on behalf of whom the prayer is made (the army, the state) and also clearly defines the purpose with maximum benefits for the referents: “strengthen, bless, multiply, save, reconcile enmity, establish peace, forgive sins to those who laid down their lives in the war for the Orthodox faith”.

Commentators on this prayer paid attention to the expression «warriors and all defenders». Andrey Kuraev asked whether it meant that in addition to the Russian Armed Forces, someone else was conducting military operations. And who might that be? He guessed that these might be the Rosgvardiya and the private feudal armies of Kadyrov and Prigozhin. (Kuraev’s FB commentary of 13 November)

The prayer is made on behalf of the arbitrarily defined referent, Holy Russia which is described both territorially (all countries of Holy Rus`, presumably including Belarus) and spiritually ‘the unity of the Russian Church’. The Russian Church is presented here as an actor responsible for the salvation of the faithful in all countries of Holy Russia. Mythmaking is typical for patriarchal hymnography.

Aleksander Kravetsky considers that the trope of Holy Rus` is a relatively late addition into hymnography. According to him, it only appears in the prayer service to Hermogen of Moscow written between 1913 and 1917, most likely under the influence of the celebration of the 300th-anniversary of the Romanov family. During this jubilee, the expression Holy Rus’ has become a synonym of the Russian state.

Furthermore, Holy Rus’ has become popularised by the sticheron from the prayer service to All Russian Saints, composed by St Afanasii Sakharov in the 1940-50s. According to Sergei Chapnin, this has become an Orthodox meme:

“The new House of Euphrates, the chosen land, Holy Rus’, keep the Orthodox faith, by it, you will be strengthened! (Rus` Sviataia, derzhi veru pravoslavnuiu)”. 3A. Kravetsky and E. Pociechina, eds. Minei: obrazets gimnograficheskoi literatury i sredstvo formirovania mirovozzreniia pravoslavnykh, Olsztyn: Centrum Badan Europy Wshodnjei, 2013, p. 85. See also J. Strickland, The Making of Holy Russia: The Orthodox Church and Russian Nationalism before the Revolution Jordanville, New York, 2013.

According to Kravetsky, Holy Rus’ is a concept that came to hymnography via the literary discourse from folklore. The active use of Holy Rus’ starts during the romantic nationalist period of Russian literature in the nineteenth century, in particular the works of Vassilii Zhukovskii, Zagoskin and neo-Slavophiles.

Therefore, the use of HR in the patriarch’s prayers suggests that it builds on the tradition associated with romantic nationalism and the period of re-sacralization of the monarchy in the last years of the Russian Empire 4 See the article of Gregory Freeze on re-sacralization of Romanovs monarchy. G. Freeze, Subversive piety: Religion and political crisis in Late Imperial Russia, Jornal of Modern history 68 (1996): 308-350. In Russian Фриз. Г. Губительное благочестие: религия и политический кризис в предреволюционной России// «Губительное благочестие: Российская церковь и падение империи. СПб: Издательство Европейского ун-та, 2019. . To be more precise, contemporary liturgical and homiletic production is a bric-a-brac activity that has no clearly articulated theological and ideological program.

A response to the official prayers by the parishes

The prayer of March 2022 was supposed to replace one that came into use in 2014, but in many parishes this prayer has not been accepted. The prayer of 2014 – with some modifications – continues to be read in the parishes of the churches under the jurisdiction of MP outside Russia, for example, in Estonia. The reason is that it is perceived as neutral, focused on the suffering subject, and any person, regardless of their position as to the war, can impose their own meaning into the words of prayer.

There is the same situation in Russia. In St Petersburg in December 2022, for example, 4 parishes continued to use the prayer adopted in 2014. In one parish, the priest reads the prayer of St John of Shanghai instead of the one proscribed by the patriarchate. In Moscow, at least one parish has completely ignored the official prayers and used the prayers of St Afanasii (Sakharov) instead. Another Moscow parish adopted the prayer of St Nicholas Velemirovich (also popular among some parishes outside Russia). Needless to say, both of these Moscow parishes are led by liberal priests.

What are the consequences for those who refuse to pay lip service to the turbo-patriotic formats of the official hymnography? Apart from Koval’s case, we know that in Moscow diocese, a parish dean has paid for his refusal to recite the official prayer by losing his post as dean (nastoiatel’stvo). The second parish priest, twice as young as the former dean, has been appointed as the parish dean.

The action of Koval’ who replaced the word ‘victory’ with the word ‘peace’ is semiotically similar to the actions of the civil activists who use the word ‘peace’ in various forms of anti-war protest.

The charges of fakes and defamation of the military forces are applied to Russian citizens who write the word ‘war’, even using asterisks and euphemisms such as vobla (dry fish) instead of the word ‘voina’ (war). However, Koval’s case is different. It challenges the patriarch’s intention to signal to the state that there is mass support for the war among the clergy and Orthodox Christians. So far, much attention has been paid to Patriarch Kirill’s homiletics, but hymnographic creativity has not yet been analysed. The reaction to the actions of individual priests sends a message to other clergy showing them the consequences. In many cases, the priests are denounced by their own parishioners or by ‘vigilant’ members of the community, as took place in Madrid.

Conclusion

Under the conditions when sociological analysis of popular opinion in Russia towards the war is not possible, the attitude of the priests within Russia towards the official position of Patriarch Kirill remains untransparent. There are different scenarios: some priests choose neutral prayers, such as the ones we have discussed earlier, others read the official prayers, and others even provide additional patriotic prayers and digital prayer space for the relatives of the soldiers.

This analysis of the hymnography of Patriarch Kirill from 2014 to September 2022 shows the change of the subject of prayer, the people of Ukraine – from the image of a family affected by internal strife (Ukraine has been seen as the same kin, but still separate from Russia), to the image of one body of Holy Rus which is penetrated by alien forces. The shift is entirely compatible with the official ideology of Putin’s official justification of the war and raises the immediate question of moral responsibility of not only the Moscow patriarchate but also individual clergy and parishioners who actively use such prayers.

- 1Petro Bilaniuk, Some remarks concerning a theological description of prayer, Greek Orthodox Theological Review (1976): 21:3, 203-214.

- 2Thanks to Andrey Shishkov who has drawn my attention to this event.

- 3A. Kravetsky and E. Pociechina, eds. Minei: obrazets gimnograficheskoi literatury i sredstvo formirovania mirovozzreniia pravoslavnykh, Olsztyn: Centrum Badan Europy Wshodnjei, 2013, p. 85. See also J. Strickland, The Making of Holy Russia: The Orthodox Church and Russian Nationalism before the Revolution Jordanville, New York, 2013.

- 4See the article of Gregory Freeze on re-sacralization of Romanovs monarchy. G. Freeze, Subversive piety: Religion and political crisis in Late Imperial Russia, Jornal of Modern history 68 (1996): 308-350. In Russian Фриз. Г. Губительное благочестие: религия и политический кризис в предреволюционной России// «Губительное благочестие: Российская церковь и падение империи. СПб: Издательство Европейского ун-та, 2019.